Introduction by Alan David Doane: We have a guest contributor for this week's Flashmob Fridays, Bubba Beasley from

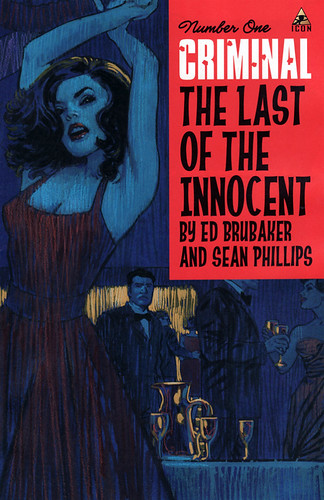

A Criminal Blog. I started ACB a few years ago ahead of the release of the first issue of Criminal by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips. I had been mesmerized by their work together on WildStorm's Sleeper series, which remains to this day a high point in the past 25 years in comics. In addition to Phillips's always lush and evocative artwork, on Sleeper Ed Brubaker proved he had major comics-writing chops by taking a character brilliantly conceived by Alan Moore (Tao, who Moore created for his Wildcats run) and utilizing him with equal, if not superior narrative creativity. If you think that's an easy feat, let me show you a few hundred bad comics by other writers who have tried and failed.

So, Criminal remains the only comic I ever felt strongly enough to create a dedicated blog around, and then Bubba Beasley came along and added his own passion and insight, and he still writes for ACB today. When looking for someone to write about Ed and Sean's latest (and very possibly greatest) Criminal emission, Bubba was the natural go-to guy. But he's not the only one weighing in on The Last of the Innocent. Members of our regular Flashmob Fridays team also have stuff to say about what I think is one of the best comics of the year, so I'll get out of the way. Let the Flashmobbing begin.

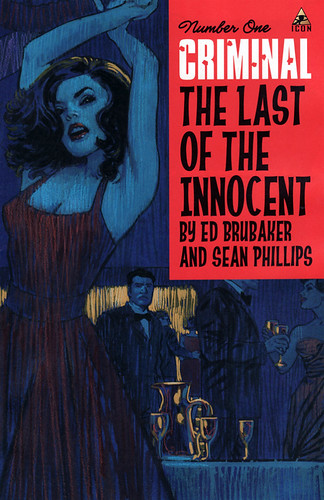

Bubba Beasley: It is remarkable that "The Last of the Innocent" may be the most critically acclaimed story arc in Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips' comic CRIMINAL. The series started very strong in late 2006, and it kept raising the bar with each of its first four arcs: the first arc introduced the introspective but brutal series, the second arc wove a different heist into every issue, the third arc presented a trio of stories that were all self-contained but intricately related, and the fourth was a surprisingly twisted thriller that worked because of careful writing rather than any cheap gimmicks.

After that, it appeared that the series might have peaked. The pair shifted their focus to two arcs of the "apoclyptic pulp noir" INCOGNITO, for which Fox acquired the film rights last year. Between those two arcs we had the fifth CRIMINAL story, and it wasn't just a sequel to the popular story "Lawless," it was a somewhat less effective retread. In both stories, Tracy Lawless investigated a murder mystery and indulged in a very imprudent affair, all while being unknowingly pursued, but in "The Sinners" these elements weren't as organic to the unfolding plot.

(Looking beyond Brubaker's creator-owned work for Marvel's Icon imprint, I've also noticed some frustration and even boredom among fans of his lengthy, otherwise crowd-pleasing run with Captain America.)

Before this latest entry, I had basically steeled myself to accept the possibility that CRIMINAL had started the slow drift from the jaw-dropping to merely the very good, and so "The Last of the Innocent" is as much a surprise as anything that has come before it. It's phenomenal even compared to the earlier, great work. It's a real achievement for Brubaker and Phillips, in more ways than most readers may realize.

1) The story arc establishes CRIMINAL as Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips' collaborative magnum opus; it's hard to imagine that their working relationship, already ten years old, will produce another work that is such a sustained and ambition project. With "The Last of the Innocent," the pair have published 26 full-length issues of CRIMINAL, finally surpassing SLEEPER's 24-issue run. There's no telling how many more stories the two will end up telling in this world. Brubaker has continued to tease "Coward's Way Out," a sequel to the debut story arc, and he may still be planning to conclude the series with the story of the crucial murder that was hinted at in "Coward."

2) The story arc defines CRIMINAL as a true anthology series set in a single, shared universe. Going by the previous arcs, one would have assumed that the series would focus on a small group of career criminals, fathers and sons. A short-story contribution to Dark Horse's 2009 anthology Noir, the CRIMINAL "emission" called "21st Century Noir" was wholly unmoored from the series' established cast and locations. With "The Last of the Innocent," we have a protagonist who was neck-deep in debts to the mob, on speaking terms with the crime boss Sebastian Hyde and his enforcer Teeg Lawless, but he's clearly not part of their organization.

The series consists of self-contained stories where the focus shifts from one character to another, and this is probably one significant reason that the series hasn't maintained a single numbering sequence through its numerous arcs. It went from a 10-issue first volume to a 7-issue second volume and finally to a series of mini-series, the idea being that new readers can jump onto every new #1 issue. This is probably why readers overlooked the milestone of its twenty-fifth issue: that issue was numbered "The Last of the Innocent" #3.

Take the trade paperback for this latest mini-series, and look at its spine. The number "6" should be there but isn't, and only the description on the back cover mentions that it is "the sixth standalone graphic novel" in the series. I'm guessing that each trade collection will be treated as an essentially self-contained publication.

I personally think the best reading order is the publication order, as one can trace the continued growth of both writer and artist. With each new arc, both tend to push themselves just a little bit further. But readers really can start with any book in the series, and "The Last of the Innocent" wouldn't be a bad introduction at all.

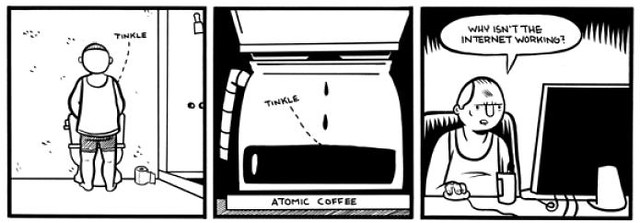

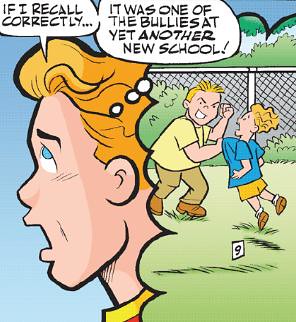

3) The story arc plants CRIMINAL firmly and almost exclusively within the medium of comic books. It was announced just two months ago that the first arc "Coward" is being adapted to film, but in a Word Balloon podcast in April, Ed Brubaker explained that this latest arc is "belligerantly a comic book," a story that could really only be told well in this particular medium. It's about comic books, in the sense that the characters riff on classic characters from comic books and comic strips: in addition to Archie and his gang, I caught analogues to Dagwood and Richie Rich, and a grown-up Encyclopedia Brown makes an appearance. It's also about the nostalgia that comic books evoke, and it uses the tropes and language of comic books to distinguish the dispiriting present from the idealized (but far from ideal) past.

I'd argue that the entire series would be difficult to adapt. It doesn't have the high concept of SLEEPER's super-powered espionage or INCOGNITO's pulp trappings, and unlike Sin City -- noir comic's other anthology series in a shared universe -- CRIMINAL doesn't use garish images to tell simple stories, both of which made it easier to condense several of Frank Miller's stories into a single, brazen film.

No, CRIMINAL is subtle and even restrained. Notice how, in both "Coward" and "The Last of the Innocent," the most brutal violence isn't shown in detail for shock value. The violence is made clear only to those paying close attention to both the images and the text.

The series' narration frequently serves as a counterpoint to the art, and the two rarely convey redundant information, but the monologue reads far better on paper than it would sound out loud. The artwork is about as realistic as Greg Rucka and Matthew Southworth's Stumptown, but I'd argue that it's much more moody, with the shadows conveying more than just physical reality and Val Staples and Dave Stewart's colors doing more than just provide visual variety -- and none of this would be easy to capture in a film or television series.

Even the structure of the series would hinder any complete adaptation. The series spans decades, which would probably require multiple actors for the same role, and it doesn't focus on a single character, ensemble, or even location. (Midway through its run, the TV series ER had cycled through an almost entirely new cast while keeping the setting of County General Hospital.)

An individual story could be captured in a single film, but would the actors' contracts include options for their cameos in other CRIMINAL films? Is it even clear how often an actor would be needed for a comic series that's still being published? An anthology series of made-for-TV movies, for a network like HBO or Showtime, would be ideal but is unlikely in the extreme.

Ultimately, a film adaptation of a single CRIMINAL story may serve the same purpose as the flashier comic series like INCOGNITO and the upcoming horror noir FATALE. My hope is that they all point potential readers to the pure crime comic and to the stories that are best suited for the medium.

4) The story arc even arguably places CRIMINAL in the same area code as the comic medium's greatest works. Before this arc, I would note that it's simply well executed. CRIMINAL is neither an autobiographical indie comic or a post-modern approach to the caped superhero, and it's not the exercise in formalism that was a major part of Watchmen or Asterios Polyp. It's a genre comic, focused on crime and noir, and it generally uses only those techniques and tools that help effectively tell an extremely well-written but sometimes conventional narrative.

Not every great work has to redefine the medium entirely. Not even every masterpiece can be a Citizen Kane, and I used to think CRIMINAL could be a Casablanca, a classic that transcends the merely competent execution.

But then "The Last of the Innocent" hit, and here we have a story that trades on literally none of the series' strength while adding layers of subtext and meaning for those who are quite familiar with the family-friendly comics of old. The conversation about CRIMINAL's place in the canon will almost certainly begin here...

...and all of this is worth noting in addition to the story itself. Beyond establishing the series' context within the creators' body of work and the medium of comics, and beyond defining the series as an anthology that was tailor-made for the medium, "The Last of the Innocent" tells one helluva crime story.

One reason the story's so good is that its protagonist is so bad.

It's easy to miss, but the story revolves around the most purely sociopathic protagonist that we've seen in the CRIMINAL universe. The story obviously plays on the theme of nostalgia, but the main character was seduced by a particular kind of nostalgia, the ache for the teenager's hedonistic irresponsibility. He didn't miss a life of innocence or true intimacy, he missed a life of getting high and getting laid, not worrying about himself or other people. Even Teeg Lawless, who would terrorize his family, was driven to commit unspeakably violent acts in order to protect his family.

Here, the creators' restraint obscures the main character's pathology so that we end up almost empathizing with him: the amoral characterization is found most clearly in what Brubaker and Phillips don't show us: in a story that is told almost entirely from the killer's point of view, the missing pieces reflect his damaged pyche.

You don't see a sense of personal responsibility on the part of Riley Richards, all-American teenager turned cold-blooded killer. You see his bad habits in adolescence and the worse habits in adulthood -- the gambling and sexual depravity (subtly shown) -- and the reader can project a path from the teenage pot use to the life-threatening gambling debts, but the path isn't even suggested. There's the idealized past, there's the bleak present, and Riley seems unwilling to see the causal chain from one to the other, to see that it was his choices that made his life miserable.

Even after he's secured his "return to innocence," Riley promises himself that he'll keep living the high life in the big city, sowing the seeds of ruin for his new life as he tried to run away from the consequences of his old life.

You also don't see any real sympathy for the people in Riley's life. He's aware of the deeply traumatic event that probably led to his wife's acting out in youth and in adulthood, but that doesn't seem to make him more compassionate toward her; he uses her in his youth, and he resents her after they marry. He may be right that people don't need an excuse to be so screwed up, but he has no charity toward people in any case.

His father who died early in the story, his widowed mother, his friends and enemies: none of their lives truly matter to Riley, and he treats them as objects to be used or obstacles to be overcome.

Even toward the end of the story, when Riley sobs after his last brutal crime, it's not clear that he mourns for his victim or merely for the self-inflicted loss in his own life.

There might be an explanation if not an excuse: you don't see responsibility or sympathy, but you also don't see a fully formed picture of a grown man who has accepted adulthood without becoming jaded. Maybe there are no good, responsible husbands and fathers in the bleak world of CRIMINAL, but if there are -- candidates such as his own father are only barely sketched -- they are entirely outside of Riley's perception.

C.S. Lewis wrote, "It may be hard for an egg to turn into a bird: it would be a jolly sight harder for a bird to learn to fly while remaining an egg. We are like eggs at present. And you cannot go on indefinitely being just an ordinary, decent egg. We must be hatched or go bad."

Maybe Riley Richards didn't see the option of hatching, so he chose to go bad.

"The Last of the Innocent" doesn't flinch from showing us how bad, but it makes the wretched man's motives understandable if not the least bit admirable. It puts a very human face on a monster.

It would deserve high praise for that even without the subtext of Archie, Betty, and Veronica. That subtext makes a great story that much more outstanding.

Scott Cederlund:

Scott Cederlund:In the comics of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips, characters like Holden Carver in Sleeper and Tracy Lawless in Criminal have all been sucked into the mire and darkness of cities where laws and are practically meaningless and powerless. "Right" and "wrong" have completely different meanings in these comic book pages. Brubaker and Phillips’s modern crime stories reflect some primal fear that the law doesn’t exist for anything other than to keep our own criminal instincts in check. They create comics about these hearts of darkness that exist in the men that are actually the heroes of their stories. Riley Richards in Criminal: The Last of the Innocent is a slightly different type of “hero” for Brubaker and Phillips. He has the same kind of blackish heart but he gives in to the darkness that Carver and Lawless spend their stories trying to rise above.

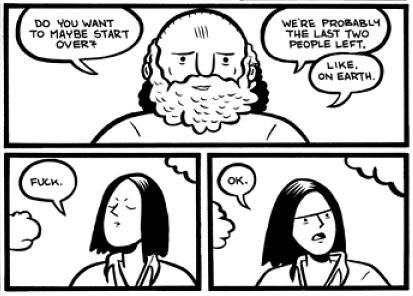

Returning to his childhood home, Richards gets swept up in an Archie Comics-like nostalgia for his teenage days. Memories of the girl next door Lizzie, his best friend Freakout, and the girl Felicity (along with her family money) he would end up marrying and even the lurid EC Comics he read with their injury-to-the-eye motifs make his teenage years seem so much better than his present where his wife’s father barely tolerates him while she’s screwing his high school rival. So Richards thinks that the way to get back to happier days is to kill his wife and return home. The girl next door and even the EC Comics are still there. His best friend is there too but Freakout (a nickname which should be some kind of indication) still fights his own demons that Richards has tried to ignore while he was wrapped up in his own life. It’s a simple plan; kill his wife and return to the girl next door without a care in the world.

Of all of Brubaker and Phillips characters, Riley Richards is the one who wins. He gets exactly what he wants. It’s not a dream and it’s not an imaginary story as Richards’s plan works to near-perfection. Even better yet, he gets his wife’s fortune, much to the ire of his father-in-law. He wins and that’s what makes Criminal: The Last of the Innocent so frustrating. Going back to the idea of Brubaker and Phillips’ heroes, the struggle between a desire to do good and an instinct to do bad does not exist Riley’s character. Once he gets the idea that Felicity has to go, there is no turning back for Riley as the story becomes about the journey to him finding his own happiness. Unlike other characters in other Brubaker and Phillips’s stories who have gotten dragged down deeper and deeper into the darkness mostly through their own weaknesses and failures, Riley’s story is about him rising up into that darkness, accepting it and controlling it so that he is never overwhelmed by the circumstances around his life. There is no failed heist or tragic death for him to try to overcome. There is no outside force manipulating Riley into actions he doesn’t want. There is only his plan and it’s all about his control of the world around him.

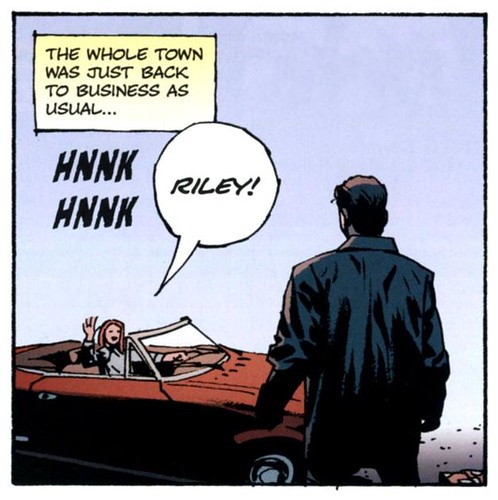

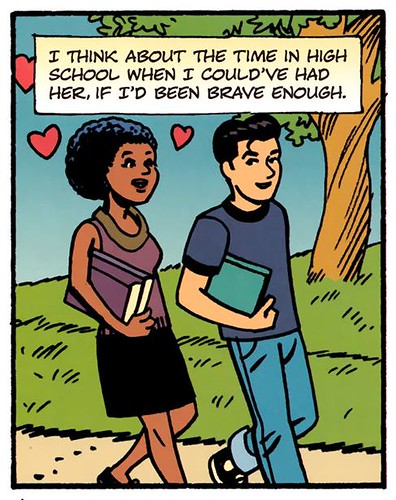

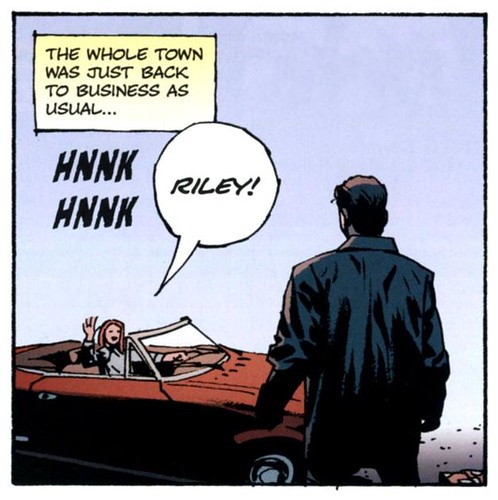

For a book about crime, Criminal: The Last of the Innocent is also about comic books in the same way that the earlier volume Criminal: Bad Night was about comic strips. In both stories, Phillips plays around with the protagonists’ views of reality and the audiences experience of their point of views. Jacob in Bad Night saw the world through the eyes of his Dick Tracy-ish character. That comic strip character was the voice whispering in the back of Jacob’s mind, pushing his action and controlling him. Riley isn’t quite that delusional but when he first sees Lizzie, for one brief moment she’s the perfect Dan DeCarlo woman, sitting behind the wheel of a convertible. While Riley’s memory of the past is filtered through Archie Comics, there’s that little bit of the present that’s still that simple and clear to him and that’s what he wants back. Other than in a dream sequence, Phillips’s scratchy reality and the clear line Archie memories never inhabit the same time space. That one moment where Lizzie brings all of the memories and feelings back to him is where she’s that perfect girl again. He sees the past as an Archie comic but he also sees Lizzie that way, a memento of an easier time.

So the killer is the hero of his own story as Brubaker and Phillips finally get to craft a Criminal story where the protagonist gets everything that he wanted. Instead of the usual sympathetic guilt we feel at the end of one of their Criminal stories, we feel a bit of revulsion as we see Riley frolic on a private beach knowing that he got away with it. Maybe it's because we're some kind of passive accomplice, not able to warn any of the victims in his way as he takes a murderous path to regain his own innocence. The Last of The Innocent is a different kind of crime story for Brubaker and Phillips. For once, they let us follow the story of a winner and it leaves you feeling guilty in the end.

Johanna Draper Carlson:I've previously reviewed Criminal: The Last of the Innocent

here, but when I did so, I resisted talking about the ending. (That's for two reasons: to avoid spoilers, and because I originally wrote about the story when only three of the four issues were out.) I'm going to discuss the conclusion here instead, so SPOILER ALERT for what follows.

When I first read the final issue of this storyline, I was disappointed by the lack of justice I perceived. Riley gets away with three murders, at least for now, and winds up with a fortune and the girl he thinks he truly loves. Then I realized that I was assuming, because this was a comic book published (however indirectly) by Marvel, that a certain moral code would be upheld, where criminals get punished. That didn't necessarily apply to a noir story. (Perhaps if I'd read any of the other Criminal stories, I'd have known better going in.)

This is also a temporary situation. We've seen, at the beginning of the book, how much Riley can screw up a good thing by, as one of the bad guys he owes money to puts it, "gambling an' whoring." Nothing's really changed about him, and the situations we've seen him go through have likely only accentuated his recklessness and stupid choices when it comes to future decisions. He's got a new temporary addiction, his new girlfriend, but how long will it take before he gets bored of her and screws things up? In such a light, the "new beginning" Riley narrates on the last page feels artificial, just like the imposition of the old-school art style over the grungy backgrounds.

The third thing I thought, and this is where I surprised myself, was "well, why not?" (This was only after the third and later re-readings, when I'd gotten over being shocked.) The promise of the modern comic industry is continual re-invention, no matter what horrible events reside in a character's past. Superman goes from being a vigilante thug to a representative of legal authority to depowered modern guy to collaborator in forced mind-erasing to young punk. Archie hangs out with the Punisher and KISS while going to prom hundreds of times and never learning not to ask out two girls at once. Given the medium, why not show a happy ending and the potential of starting anew, regardless of one's past?

The question now is, how believable do you find Riley's assertions when he's been lying to himself and others the whole story?

Joseph Gualtieri:In

A Poetics of Postmodernism: History, Theory, Fiction, Linda Hutcheon repeatedly refers to parody as being perhaps the key characteristic of postmodern art, “the perfect postmodern form...for it paradoxically both incorporates and challenges that which it parodies” and that “Parody seems to offer a perspective on the present and the past which allows an artist to speak to a discourse from within it, but without being totally recuperated by it.”

Criminal: Last of the Innocent by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips is a parody of Archie Comics in general. That’s nothing new, of course, given the age of the franchise. The most notorious parodies of it are probably “Goodman Goes Playboy” by Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman (available for free on the Comics Journal website) and Weird Comic-Book Fantasy, a play by future comics scribe Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa originally titled Archie’s Weird Fantasy until a lawsuit forced changes to it (if anyone knows how to get a copy, please leave a comment below). As with Kurtzman and Elder, Brubaker and Philips add explicit sex and drugs to the Archie milieu with Last of the Innocent, but their parody goes far beyond such crude humour.

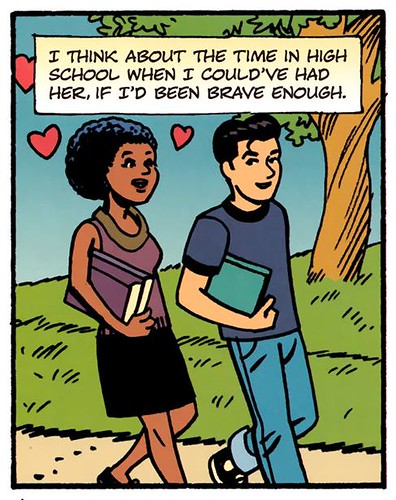

The bulk of the Last of the Innocent occurs in 1982, but it frequently flashes back to the late 1960s in a deft technical maneuver. In past Criminal volumes, Brubaker and Philips have used a comic strip within the comic, Frank Kafka, Private Eye, as a counterpoint to the action (and in the fourth and best volume, they introduce us to the creator of the strip). They reprise that device here in a more complex way by providing one-and two page flashbacks that are also presented as gag pages or scripts from “Riley Richards” comics illustrated by Phillips in a faux-Dan DeCarlo style. The first few of these flashbacks are largely in the “Goodman Goes Playboy” mode of adding sex and drugs to the characters, but two pages from the end of the first issue has the first real break from portrayal of an idyllic past in the flashbacks, as Richards remembers finding a dead body along with Freakout (the Jughead character). To bring Hutcheon back, the flashbacks are the primary way Brubaker and Philips, parody Archie, offering a clear way to “incorporates and challenge” the source material.

The next issue Richards makes his way into the local police records to research the death, which was part of a series, with the aim of framing his wife’s lover for her murder as well as the unsolved ones from the past. Serial murder would, on the surface, seem to be just one more element added to Brubaker and Phillips’s sordid version of Archie, but the way they use it is devastating. The discovery of the dead body comes during a long monologue by Richards worth quoting at length:

That night I have the weirdest dream… I’m flying over Brookview… But the town is the same as when I was a kid...Like I’m a tourist in my own past [...] I see all the lazy Sundays in the world. And I have this strange feeling... that I can go back and fix all the mistakes I made. Like I could do it all over again. And be back in the warmth of those endless summers...

Immediately after waking from the dream, Richards resolves to kill his wife, Felix/Veronica. There’s a clear connection here between Richards’s romanticized view of the past and the murderous decision that drives the rest of the series. Further, this is the opposite what Brubaker and Phillips do; for the creators, the flashbacks are a way for offering comment on the source material, for Richards, memories are something to wallow in and wish for an imagined Golden Age, not gain perspective.

In the final issue, the second to last flashback is from Freakout’s perspective and reveals the truth behind the 1960s serial killing — that they were done to provide cover for a couple carrying on an affair to murder the woman’s husband. Discussing the matter with Richards, Freakout tells him that they (and the police) were the only people who knew the murder weapon. Richards is rendered silent for a panel and then admits, “Actually, I forgot about that part...” His memory is exposed as not just idealized, but factually incorrect. Richards commits a second murder, leaving a tainted syringe for Freakout, and returns home to Lizzie/Betty, concluding “the last person — maybe the only person — who really knew me...is lying on a slab in the Brookview County Morgue. So now I can be whoever I want,” as the art shows Richards and Lizzie in Phillips’s usual style slowly transform into the faux-DeCarlo style even as the world around them doesn’t change.

Towards the series’ end, Richards and Lizzie are living in a beachfront house that once belonged to Felix, he thinks, “I always knew coming here with Lizzie would be better,” which is in marked contrast to his memories in issue two, where he’s sexually active with Felix while Lizzie will barely do anything with him of that nature. Looking in on a sleeping Lizzie after a day of sex at the beach house, he thinks, “How can she have stayed so pure. I hope some of that will rub off on me...” Lizzie is “pure” because she’s barely a character in the comic. Beyond asking her about dating one old classmate, Richards makes no inquiries about how she’s spent the last decade or so; he treats her as if she’s spent the whole time waiting for him, and can restore the false the innocence to him that he so longs for.

I can scarcely imagine a more devastating critique of Archie Comics than the one Brubaker and Phillips provide in The Last of the Innocent. While that franchise has always taken place in the present, it’s usually been a backward, delayed sort of present (as Flashmob Fridays readers know, Riverdale only recently had its first gay citizen move in). The Last of the Innocent exposes the cost of the nostalgia inherent in the property. It’ll survive this broadside, just as it did “Goodman Goes Playboy” and Archie’s Weird Science; that in no way decreases the power of Brubaker and Phillips’s work. They engage fully with Archie here, and delve deep within it and expose the hollow core to it like no one else.

Buy Criminal Vol. 6: The Last of the Innocent from Amazon.com.

Aided by his best partner, Sean Phillips, Brubaker accessorizes this seedy melodrama with a series of one-page gag strips drawn in a style reminiscent of Archie Comics. And indeed, the characters themselves are stand-ins for Archie Andrews (Riley), Veronica/Ronnie (Felicia/Felix), Betty (Lizzie), Reggie (Teddy), and Jughead (Freakout), as well as amusing but not distracting nods to Moose, Mr. Weatherbee, and Valerie of Josie and the Pussycats. Brubaker has Phillips draw the gags in this similar, brightly colored style to emphasize how much simpler Riley's life was as a teenager, but he cleverly counters this conceit with the gags always revolving around either pain or seedy activity. Darker parodies of all-ages comics fare have been with us since Tijuana Bibles, so it's fortunate that Brubaker exercises restraint in their use here, and in fact, confining each flashback to a one page gag tends to sharpen his focus. However, while the Archie motif will certainly grab the attention of most fans, even those with only vague knowledge of Archie, what stood out for me was how sharp Brubaker's narration and dialogue was throughout the story. There is hardly a line or observation from Riley that doesn't reverberate with pain or self-loathing. We feel for Riley, up to a point, but his actions are unforgivable, particularly towards the innocent fool, Freakout, and so it makes Brubaker's seemingly happy ending all the better, because by now we know that Riley is the type of person who will find a way towards misery again.

Aided by his best partner, Sean Phillips, Brubaker accessorizes this seedy melodrama with a series of one-page gag strips drawn in a style reminiscent of Archie Comics. And indeed, the characters themselves are stand-ins for Archie Andrews (Riley), Veronica/Ronnie (Felicia/Felix), Betty (Lizzie), Reggie (Teddy), and Jughead (Freakout), as well as amusing but not distracting nods to Moose, Mr. Weatherbee, and Valerie of Josie and the Pussycats. Brubaker has Phillips draw the gags in this similar, brightly colored style to emphasize how much simpler Riley's life was as a teenager, but he cleverly counters this conceit with the gags always revolving around either pain or seedy activity. Darker parodies of all-ages comics fare have been with us since Tijuana Bibles, so it's fortunate that Brubaker exercises restraint in their use here, and in fact, confining each flashback to a one page gag tends to sharpen his focus. However, while the Archie motif will certainly grab the attention of most fans, even those with only vague knowledge of Archie, what stood out for me was how sharp Brubaker's narration and dialogue was throughout the story. There is hardly a line or observation from Riley that doesn't reverberate with pain or self-loathing. We feel for Riley, up to a point, but his actions are unforgivable, particularly towards the innocent fool, Freakout, and so it makes Brubaker's seemingly happy ending all the better, because by now we know that Riley is the type of person who will find a way towards misery again.