Introduction by Alan David Doane:The greatest minds ever to create comics -- I'm thinking of creators like Jack Kirby, Alex Toth, Gil Kane, Robert Crumb,

Bernard Krigstein,

Carl Barks, Alan Moore, and of course,

Harvey Pekar -- all rose to prominence, won the respect of readers and other writers and artists, and guaranteed their places in the history of comics because of one common element: Each of them showed the rest of us that there were possibilities in comics that no one had seen until they carved out the path. Toth showed how much you could do by showing only the bare essentials; Krigstein showed how breaking out of the expected box could lead to an infinite fractal complexity on the comics page. Barks demonstrated how powerful the wedding of children's characters and inventive storytelling could be; Moore taught those willing to learn how to use the power of imagination to create new heights of majesty in comics writing.

And then there's Harvey. Sure, there had been a few autobiographical or semi-autobiographical works created in comics before Pekar first began writing scripts about his life and times on the streets of Cleveland. But almost immediately, those with a vested interest in comics as an artform saw that there was an entirely unsuspected potential to be found in speaking plainly but thoughtfully about moments as common and diverse as waiting in line at the supermarket, crashing your car in the snow, or finding out you have cancer. By depicting and examining his own everyday existence in nearly obsessive detail, Harvey Pekar somehow tapped into a universality of the human spirit in a way that elevated the artform of comics higher than it otherwise would ever have risen. On a large scale, the potential of storytelling in comics form is greater now than it was before Harvey first set pen to paper. On the smallest scale, that of the individual reader, I know that my life has been improved, my spirit touched, my intellect challenged and rewarded, because this one file clerk in Cleveland made up some comic books about his life.

There is, in fact, no one in comics whose work I love more than I do the comics of Harvey Pekar. There may be a few I hold in equal esteem (pro tip: check out that list in paragraph 1), but no one has ever exceeded Harvey's reach. Few have even attempted to scale his heights, never mind done so for four decades. That Harvey did so for so little financial reward is kind of amazing and speaks to his tenacity as a human being. He knew comics was an artform, he knew his work was important (although it never, ever felt

self-important), and I suspect he sacrificed a lot to bring his vision to life again and again, especially in the earliest years of self-publishing, long before comics and book publishers came calling.

Harvey liked to say comics are just words and pictures, and that you can do anything with words and pictures. We know that's true in large part because

he proved it. I often think of him, and I hope that the respect and attention he garnered late in his career, especially after his American Splendor comic book became

American Splendor the movie, was enough for him. I hope he knew how much we all loved his comics. I hope he knew how much we all loved

him. Never before and never since has comics produced a Harvey Pekar. And never again will Harvey Pekar produce comics. Cleveland is his last work, and I'm very pleased that it's the subject of this week's Flashmob Fridays.

Christopher Allen:What I believe is the final completed work by the late author Harvey Pekar is now available, an expansive memoir that also performs about half of the time as a history of Cleveland, Ohio. The so-called navel-gazing, emo, whiny autobiographical comics of the ‘80s and ‘90s were never as large in number as detractors claimed, but what there were always found an antidote in Pekar’s comics, which addressed disease, relationship and work problems with either a crusty humor or resolve, a get-it-out-and-over-with quality that Pekar brings to this finale project.

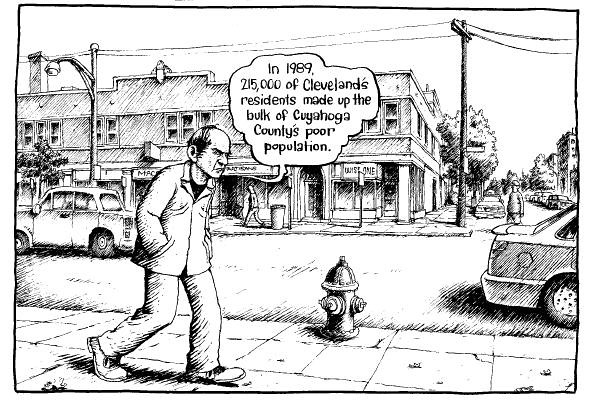

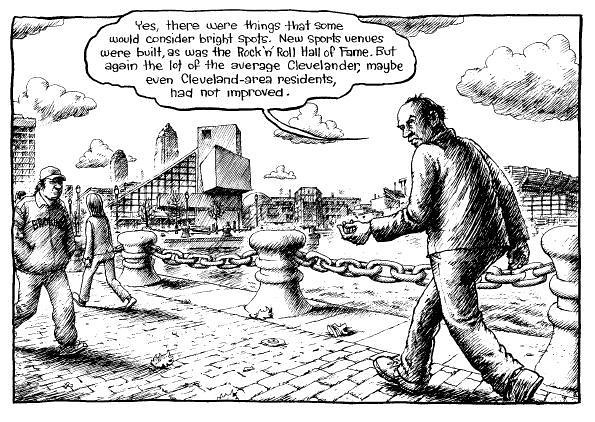

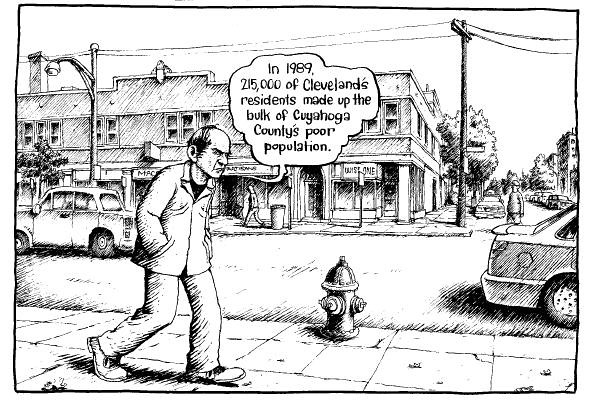

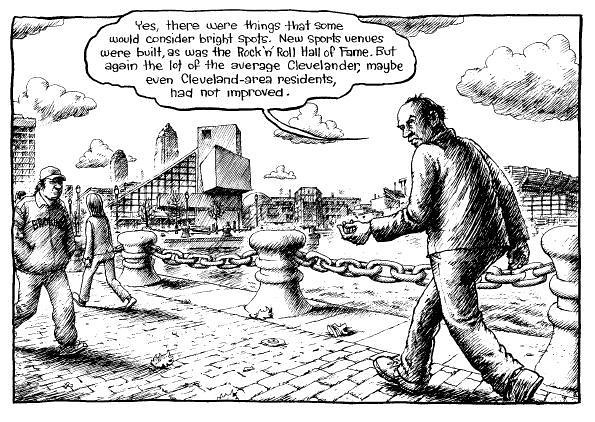

After some uneven work the past several years, such as the overrated graphic novel, The Quitter, a detached nonfiction look at Macedonia, and a Vertigo miniseries that more often than not found him unable to polish mundane anecdotes and observations into bright gems of humanity, it’s fitting that Pekar ends on familiar ground, just him and his beloved hometown. That said, much of the history of Cleveland, as told by Pekar, is not all that interesting, and while it seems fairly well-researched, some observations are arbitrary and inconsistent. For instance, African-Americans seem to have an above-average quality of life compared to other cities, for a while, and then by the ‘60s there are several riots, without much explanation how things deteriorated. What industries’ or athletic teams’ declines, or other factors contributing to Cleveland’s decline and lack of growth, are not examined. Which is fine; no one should expect this to be a definitive history, but one should understand that this is Cleveland through Pekar’s eyes as a lifelong resident, a working class, self-educated writer whose lens is focused more on the city’s cultural history as it happened to him, its great library and symphony, its jazz clubs, used bookstores and parks. If you’re interested in Cleveland’s rock and roll history, great restaurants, organized crime or political history, this is not the book for you.

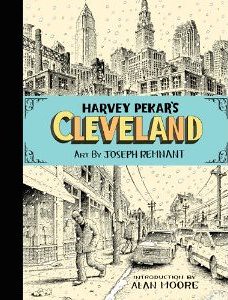

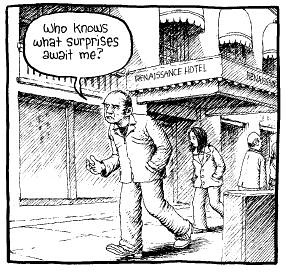

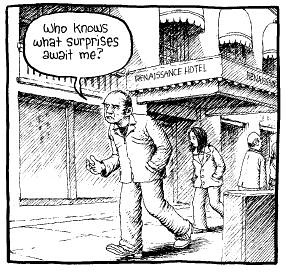

Pekar has worked with some good artists before, but Joseph Remnant (and how ironic is that name for the artist of Pekar’s last book?) is really ideal for this material. Fairly realistic, not too stylistic, and with a warm crosshatching style that works well with Pekar’s prose to capture Cleveland’s past and present with both clarity and fondness. His figures are gently slope-shouldered, reminiscent to me of great children’s book illustrator Mercer Mayer (The Great Brain, Little Critters), which works very well in most of the book, aside from maybe the riots, which call for something a bit more dynamic. Remnant’s Pekar is cuddly without being a caricature. The only real issue is how often to include Harvey in the art and how often to just let him narrate, which results in odd choices like Harvey talking to the reader while sitting on a moving subway. It was probably Pekar’s choice to include himself periodically, but it seems unnecessary, as his voice is always distinct and present in the narration. It’s easy enough to just see the art as if one is looking through Pekar’s eyes, so there’s no much need to actually see him shuffling around the city.

Ultimately, although there is some merit in the historical portions of the book, the most compelling material is autobiographical, with young Harvey making friends, discovering a love of reading, scholarship and collecting, and some material on girlfriends/wives (much of which has been explored at greater length in prior American Splendor work), as well as a bittersweet conclusion that finds Pekar working hard in retirement to make ends meet, even as his intellectual curiosity has cooled. Maybe my favorite part was learning that as a middle-aged man, he immersed himself in literary scholarship out of spite for his ex-wife, which struck me as hilarious, practical, and totally Harvey. Not the best book he’s done, but well worth reading.

Roger Green:

Roger Green:Don't know just when I started reading Harvey Pekar's American Splendor, but it was definitely in the early period of his self-publishing mode in the late 1970s, with art probably by Robert Crumb. I totally identified with the main character, which of course was Harvey himself, a caustically sharp observer of the human condition, especially his own. But, in my comic book drought days, I had never read his later works published by Dark Horse or DC/Vertigo. (I did see, and love, the 2003 film of the same name.) I actively never watched him on Letterman, because I thought Dave would treat him as a buffoon.

So reading Cleveland was rather like going to a college reunion. Would I still like this guy? Would he still be as clever and pointed as that fellow I once knew? And when you read Harvey, you DO feel that you "know" him.

The book starts with a lengthy history of the title city. I got a bit impatient with it, not so much because of its length but because there wasn't enough of Harvey's voice there. I did, though, understand the point of some of this section, especially as it related to baseball and race relations, because when we FINALLY get to the Harvey part - on PAGE 43! - the context of the some of the earlier stuff begins to make more sense.

And it's in these next 80 or so pages that I said, "There's the Harvey I remember," analyzing his complicated relationship with women, how having losing sports teams gives a city an inferiority complex, his hoarding behavior with books and music, his work history, the value of the public library, and his staged blowup with Letterman.

The latter pages are bittersweet as he muses, in the words of Paul Simon, "how terribly strange to be 70." What will his future be like? Unfortunately, Harvey never made it to 71. Still, I was glad to spend one more round with an old friend.

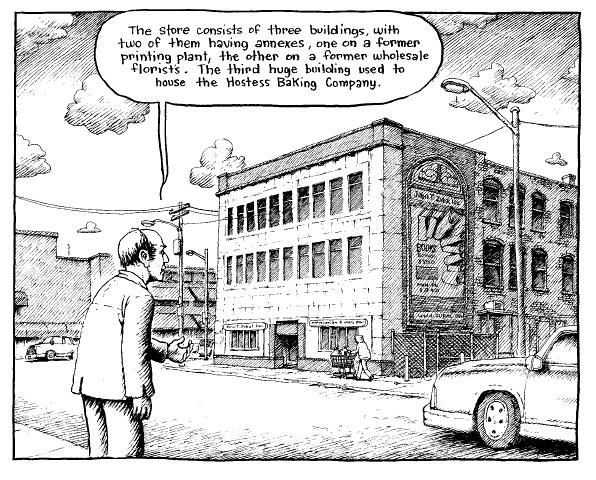

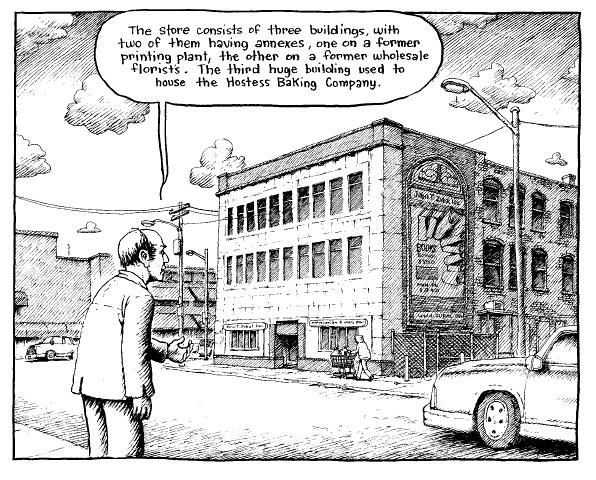

Scott Cederlund:A city where the sweet Twinkie filling flows freely out of pipes sounds like some magical place like Willie Wonka’s factory. The truth is that such a fantastic place exists in Cleveland, one of America’s historical cities that’s a sad shadow of the city it once promised to be. The building where Twinkie filling still runs trhough the pipes, a one-time Hostess factory now converted into a giant used book store, is a re-occuring set piece in Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland, a book about a city the author lives in as much as it is about the author himself. Over the years, Pekar has become synonymous with Cleveland. One almost doesn’t exist without the other. When Anthony Bourdain took his Travel Channel show to Cleveland a few years ago, he had to have Pekar on the show. For Bourdain, like so many others, Pekar

is Cleveland.

Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland begins as a hopeful dream. Pekar and artist Joseph Remnant begin the book in 1948 when the Cleveland Indians won the World Series. “Yeah, I’ve had plenty of good days,” Pekar muses, but the best was still the day when he was eight years old listening to the game over his school’s P.A. system. To this kid, sports were everything and his entire civic pride was wrapped up in his baseball team. Pekar regales his audience with stories of Cleveland Indian baseball from the late 1940s and early 1950s before delving into the history of Cleveland. Beginning from the earliest days in 1795, the desires for the city were always countered by a stark reality. Even as the city, more of an outpost then, began to grow along the Cuyahoga, the river itself became a source of disease and insects.

As Pekar chronicles the history of the city, for every success there is an equal or greater failing that the city experiences. His recounting of the 1948 World Series at the beginning of the book perfectly introduces this pattern. They won in 1948 but the Indians would go on to lose the 1954 World Series. It would take them another 40 years to reach the World Series but they lost twice during the 1990s and haven’t been back since. “For me,” Pekar writes, “the 1954 World Series was a turning point. I always looked at the Indians as an up-and-coming team. But now they seemed to be rotten to the core with success... A few years later, that’s how I viewed Cleveland: rotten.”

That’s the viewpoint of a kid but this book easily shows that Pekar’s feelings for the city are a bit more complex than that. By Pekar’s account, there always seems to be something eating away at the city and its people. For every step forward, there were two or three back. So maybe even if the city’s core is rotten, Pekar still finds the good in it. He finds the bookstores with Twinkies filling in the pipes. He finds the people and the joy in the city even as he recognizes all of the missed opportunities that exist for Cleveland and for himself.

For a book about a city, about halfway through the book Pekar takes a side path and begins talking about himself and his own life. It starts out as a diversion but it becomes the second half of the book. In it’s own way, that’s typical Pekar as so much of his work is autobiography but it also illustrates the relationship of the man and his city. As much as he can see both the good and the bad in his hometown, he expresses the same about his own life. There are loving but absent parents. There are wives but there are also divorces. There is cultish fame but it never translates into book sales. There is happiness but there is also cancer.

Remnant brings the whole book together, drawing Cleveland and Pekar showing their warmth and their warts. He doesn’t gloss over anything that Pekar writes, instead showing the life of the man and the city with the honesty and openness that Pekar expresses in his writing. Remnant also gives the book its steady foundation. Pekar is all over the place in his narration and feels unfocused. Is this a book about the city or the man? Pekar never makes clear his intent as he wanders from one moment in time to another as easily as wandering from one city block to another. Remnant keeps up with Pekar, shifting from the historical recounting of the 1800s to the 1970s when Pekar is talking about his own search for love and friendship. Pekar wanders in this book, starting in one place, going off in a tangent but bringing it all back together and never straying far from Cleveland.

In the end, Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland is a bittersweet book. Two entities, man and city, are so intertwined and yet neither one is able to have the success or satisfaction they desire. This book could just as easily be titled Cleveland’s Harvey Pekar because their stories are split almost in half in this story and their stories are thematically so similar. One becomes a metaphor for the other. Pekar was great at making the mundane entertaining and enlightening but here he also makes the mundane sad but optimistic. He’s so discouraged by the city and life around him but he’s also so optimistic that tomorrow may be just a bit better than today. The city may be rotten to the core but as long as Twinkie filling flows through the pipes, there’s a bit of magic in this town and maybe the Indians will win next year.

Johanna Draper Carlson:

Johanna Draper Carlson:Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland, illustrated by Joseph Remnant, is the quintessential Pekar autobiographical graphic novel, a love letter to his hometown that unblinkingly looks at the bad as well as the good. Pekar's narration intertwines moments and memories of his life with incidents that demonstrate the downfall of what was once an industrial powerhouse.

I've never been able to really get the appeal of Pekar before. There was too much crotchety old man complaining about it, but here, the setting gives the work more of a hook for me. Looking at his life, even when he's grumbling, as a parallel to the downturn of a great American metropolis puts things in perspective. Plus, I now better appreciate the viewpoint of someone older and with experience; I think of his comments as having more perspective. Having seen how a community can decline, some grumpiness is understandable.

Remnant's work is a perfect choice for the material. It's straightforward, well-suited to the journalistic approach, but has its own character. Instead of simply drawing what we're being told, the illustrations add to the story by fleshing out the text and providing a real sense of place and time.

Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland is a fitting final work by the curmudgeon who made comic autobiography into the powerhouse it is today, as well as a wonderful starting point for anyone wanting to sample his work.

Buy Harvey Pekar's Cleveland from Amazon.com.

Buy Harvey Pekar's Cleveland from Amazon.com.

I actually thought A Boy and His Dog by Bren Collins was "real". And from then on, the level of storytelling improved quite a bit. Some stories I liked, others, not quite, but the percentage of positive tales was higher than the duds. Things That Go Bump in the Night by Aaron Brassea gave me a mild chuckle. A Bigfoot Adventure by Jeffrey J. Manley went on too long for the joke, and had some production problems on one page, but had potential. Big Bad Wolf by Clifton Chandler had an interesting wood carving effect.

I actually thought A Boy and His Dog by Bren Collins was "real". And from then on, the level of storytelling improved quite a bit. Some stories I liked, others, not quite, but the percentage of positive tales was higher than the duds. Things That Go Bump in the Night by Aaron Brassea gave me a mild chuckle. A Bigfoot Adventure by Jeffrey J. Manley went on too long for the joke, and had some production problems on one page, but had potential. Big Bad Wolf by Clifton Chandler had an interesting wood carving effect.